Blind-Solving NYT Strands with Algorithms (Part I)

Winning Without Understanding

In July 2015, New Zealander and Scrabble GOAT Nigel Richards won the French Scrabble Championship. The win was particularly impressive because Nigel was not a French speaker. He simply memorized all 386,000 words in the French Scrabble dictionary.

I drew inspiration from Mr. Richards to tackle Strands, the latest addition to The New York Times word games line up, with a similar approach: Solve the puzzles without any direct interaction with the game board or knowledge of the English language.

The algorithm uses the game grid and a list of accepted words to derive solutions. In backtesting, the algorithm successfully solved 88 out of 91 puzzles published since March 4th, 2024, averaging 9.73 seconds to find a solution.

This post outlines the problem definition and formulation. Part 2 will describe the specific implementation details. The algorithm is available in a public github repo here.

The Rules of the Game

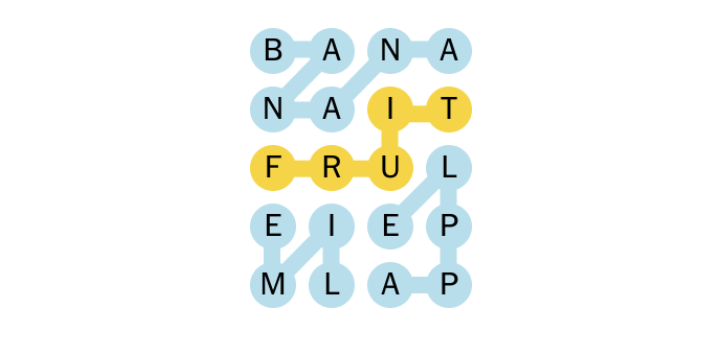

At a glance, a Strands board looks like the word search games found on an IHOP menu — a rectangular grid of jumbled alphabet characters. The objective is to identify all thematically linked words on the board. Upon completion, these words fill the grid entirely, without overlap.

Here's what a typical game looks like for a human player:

- Read the theme hint and search the grid for related letter combinations.

- Submit guesses whenever a valid word is identified, with correct ones highlighted.

- As more words are found, the game simplifies, narrowing the search space and clarifying the theme.

We benefit from our inherent semantic knowledge, a capability that our robotic counterparts have arguably yet to fully develop.1 Meanwhile, computers excel in making repetitive comparisons and working long hours. The algorithm will leverage these strengths.

Defining the Problem

We begin by operationalizing the Strands puzzle into a computational model of inputs and outputs.

Inputs include:

- A two-dimensional letter matrix of the game board

- A lexicon of accepted words

The output:

- A valid solution comprised of paths - sequences of coordinates - that spell out words in the lexicon.

- Paths as a whole traverse the game board, covering each square exactly once. In other words, the paths form a MECE (mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive) partition of the board squares.

Additional specifications regarding the deliverable:

- The solution must be found in a reasonable amount of time. Limit initially set to 10 minutes.

- The algorithm will be optimized for a typical NYT Strands game: an 8 x 6 letter grid with an accepted vocabulary of ~200,000 English words.

- Solutions are expected to follow a pattern similar to past published games. This point may seem minor, but becomes a crucial element in the optimization process.

Establishing the Baseline with a "Dumb" Method

A naive brute-force approach will be our baseline. The method starts from any random letter and searches all eight directions (cardinal and diagonal) to form a valid word. The process is repeated until the board is complete or no further words can be found.

This method is obviously slow. In the worst case, a single word can have a complexity of roughly O(8^mn). Assessing configurations of multiple such words is practically impossible.

Some observations for improvement:

- It's unnecessary to consider every possible letter combination in the board, as only a small subset will form the valid words in the lexicon.

- The order of the words does not matter. A player may find the correct solution scanning from top to bottom, just as another could arrive at the same result by playing in reverse.

We can leverage this knowledge to reduce the initial task into a problem that is better defined, one that is much more familiar.

NYT Strands is a Set Cover Problem

Imagine a big old box of jigsaw puzzles. If we mix in a new puzzle set into the box, how do we get them back?

Strands has a similar objective. Given a collection of word pieces, players must find the combination that perfectly fits the rectangular game board.

By precomputing all possible words on our game board, we can prepare the box of puzzle pieces in advance. This puzzle can now be reduced into the set cover problem, a classical combinatorics question.

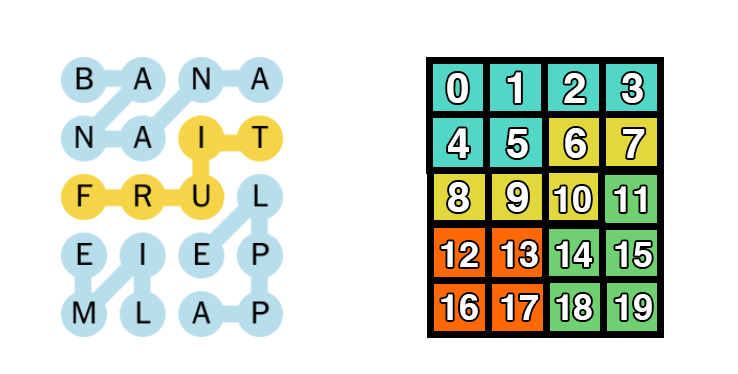

Suppose we assign a number index for each square on our game board. Then each word can be represented as a set of integer indices. Thus, we can show that solving Strands is roughly equivalent to finding a set cover whose components do not overlap.

The Devil's in the Details

Reducing our puzzle to a known problem allows us to stand on the shoulders of giants. Still, set cover is an NP problem and it's challenging to find an efficient solution.2

When I was taking algorithms courses as a student, "NP" used to feel like a death sentence. Deeming the task impractical, I'd take out a pencil and paper to write proofs instead of code.

Later on I found that life's full of NP problems like Strands and that working on them is actually an exciting endeavor. NP lies on the fringes of feasibility, meaning that each implementation decision has the power to make or break your algorithm.

In Part 2, I will detail the optimization tactics I employed to improve the runtime from 10 hours to 10 seconds.3

In the meantime, the algorithm still has significant room for improvement. Suggestions, forks, and pull requests are always welcome.

Footnotes

-

Word embeddings can serve as a decent proxy. Quantifying semantic information will be explored in greater detail in a future post on NYT Connections. ↩

-

The minimum set cover problem has a relatively efficient approximation algorithm, but is not helpful here since we need to exhaustively search all combinations. One possible avenue is to convert the puzzle into a weighted set cover problem by assigning "weights" to each word based on their distance to the theme hint. ↩

-

A sneak peek: tries, bitmasks, memoization, backtracking, parallelization, and more! ↩